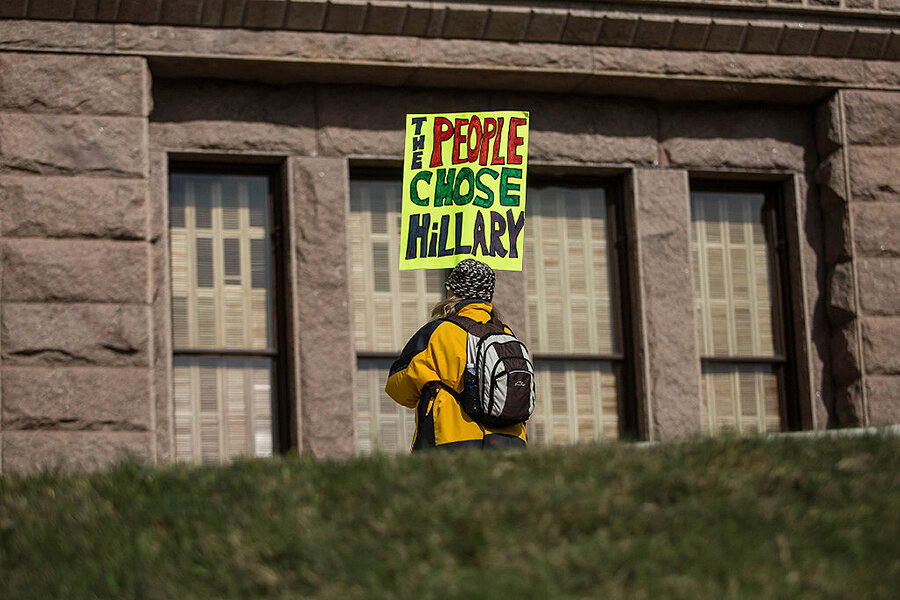

Clinton wins US popular vote by widest margin of any losing presidential candidate

Loading...

Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by the widest margin of any losing candidate in US presidential elections history, carrying nearly 2.9 million votes more than President-elect Donald Trump, according to an Associated Press analysis of certified results from all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Despite his comfortable win in the Electoral College, which formally elected him Monday, Mr. Trump has repeatedly criticized his opponent's lead in the total count of overall votes.

"I would have done even better in the election, if that is possible, if the winner was based on popular vote - but would campaign differently," Trump wrote in a series of tweets Wednesday, noting that his accomplishment was "much more difficult & sophisticated" than winning the popular vote.

The comments came nearly a month after Trump asserted, without evidence, that he had actually "won" the popular vote, "if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally."

That assertion was immediately challenged, and no evidence has surfaced to substantiate it. But the notion that widespread voter fraud is to blame for Clinton's popular vote win still lingers.

Despite widespread media reporting on the election's preliminary outcome, a majority of Republicans – 52 percent – told pollsters, incorrectly, that Trump had won the popular vote as well as the Electoral vote, as The Christian Science Monitor's Gretel Kauffman reported last week:

The poll highlights a common theme throughout the 2016 presidential election lamented by those on both sides of the partisan aisle: a widespread rejection of facts in favor of ideas that confirm one's own pre-existing political bias. The phenomenon, reflected in a record high distrust of the mainstream media and the proliferation of fake news on social media, has been exacerbated by the candidacy of Donald Trump, who, since the start of his campaign last year has made frequent false claims and emotional appeals to his supporters while denouncing facts as conspiracies concocted by the other side.

The AP analysis of certified results showed Clinton winning 65,844,610 votes, or 48 percent, with Trump winning 62,979,636 votes, or 46 percent. Those results make Clinton the fifth presidential candidate in US history – and the second this century – to win the popular vote and lose the Electoral College. (In 2000, Democratic nominee Al Gore lost, despite carrying 540,000 votes more than President George W. Bush.)

Instead of electing their president directly, Americans technically vote for state electors, who then formally cast ballots on the public's behalf. Neither the US Constitution nor federal law requires these electors to vote in accordance with their state's popular vote, but some individual states have imposed such a requirement.

Some groups argue that the Electoral College exists as a check on the democratic process to prevent an unqualified candidate from making it into the White House, which is why groups recently lobbied individual electors in hopes of dissuading them from voting for Trump, as the Monitor reported:

The argument behind the lobbying is that Trump is the kind of candidate the Founding Fathers worried about. His character is suspect, according to his critics, as shown by his bizarre tweets, rambling speeches, and constant disregard of facts. Russian hacking might have swayed the election, they add, and Trump’s foreign business entanglements seem worrisome.

The Electoral College exists to coolly vet the people’s choice in light of the national interest, in this view. Alexander Hamilton would reject Donald Trump, opponents argue, not because of his policies and what he wants to do, but because of who he is.

The lobbying efforts failed. Trump won 304 electoral votes to Clinton's 227 votes when electors cast their ballots Monday in their respective state capitals. But there were more defections, or so-called "faithless electors" who voted for someone other than the candidate their state selected, than during any election in the past century.

There had been only eight faithless electors since 1900, each in a different election. This year, there were seven defections. Most of them, however, were on the Democratic side.

Only two Republican electors broke ranks, both in Texas. One voted for former Libertarian candidate Ron Paul and the other for Ohio Gov. John Kasich, who had competed against Trump in the primary.

Among Democrats, there were five faithless electors, including four from Washington State. Three voted for former US Secretary of State Colin Powell, a Republican who supported Clinton, and one voted for Faith Spotted Eagle, a native American elder associated with the Dakota oil pipeline protests.

In addition to their historic popular vote margin, Democrats made history this year with the largest number of elector defections since 1872, when 63 electors declined to vote for Horace Greeley, who had died. Ulysses S. Grant had won re-election by a wide margin that year.

This report contains material from Reuters and the Associated Press.